|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

FMS FEATURE ARTICLE... February 6, 2004 Part I Richard Shores Remembered A look back at the life and career of a remarkable composer by Jon Burlingame

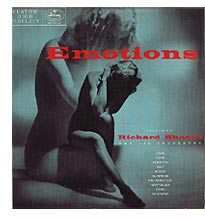

Shores died quietly at his Encino, California home on April 12, 2001, the result of complications from a stroke. No formal obituary was published and, because he had lost touch with colleagues in the film-music community, his passing was known only to family and close friends. (A check with ASCAP officials revealed the news only recently.) Unfortunately, Shores didn't live long enough to see the best of his U.N.C.L.E. music released on compact disc in late 2002 and 2003, and a surprising number of fans publicly expressing their admiration for the composer's unique contributions to television. Shores came along at just the right time, as the studios were creating a huge amount of original music for TV series of the '60s and '70s. He was a craftsman of the highest order, able to write for any ensemble and in any genre - but what was unusual about his music was that, by the late 1960s, he had developed a personal style that was almost always immediately recognizable. "He was a thoroughly accomplished musician," says Richard Berres, who as vice president of music at Columbia during the mid-1970s regularly hired Shores for various series and TV-movies. "He was the most underestimated composer in Hollywood," notes Don B. Ray, longtime music supervisor at CBS, where Shores spent most of the late '60s and early '70s. "His use of the orchestra was brilliant." Adds woodwind player William Calkins, a regular in Shores' orchestras: "He was a very talented composer. He had a great gift for expressing what was on the screen, whether for action or romance." Richard Warren Shores was born May 9, 1917 in Rockville, Indiana. He studied composition and piano at Indiana University and during that time he became conductor of a chamber orchestra as part of a Works Progress Administration theater arts music program in Indianapolis ("the greatest thing that ever happened to me," he said in a 1991 interview). Then, on an ASCAP fellowship, he attended the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, where he received his master's degree in music under the esteemed Howard Hanson. During World War II, he served as a staff arranger for one of the largest bands in the country, the 150-member ensemble at the Jefferson (Missouri) Air Force Base. He also served overseas, and was among the soldiers who helped to liberate the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945. After the war, he went to Chicago to pursue a career in music. "I did everything in Chicago," Shores said, "arranging, composing, a lot of scores for industrial pictures, recording work. I worked in radio, and I did some [live] television when television was brand new, around '50 or '51." Some of Shores' early efforts were commercially recorded, among them Paul Bunyan, based on the children's tale and written for a 1952 exhibit at Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry; Behind It All, a fine orchestral score for a Universal Oil Products short; and two love ballads, "Then Something Happened to Me," sung by the now-forgotten Elaine Carvell, and "Too Soon," performed by well-known jazz vocalist Sue Raney. Shores' arrangement of the vocal version of Max Steiner's classic Gone With the Wind theme, "My Own True Love," for singer Johnny Desmond, was a top-25 hit in late 1954.  It was a record album that launched Shores' career in Hollywood. Mercury Records, in early 1957, released an orchestral LP called Emotions (Mercury MG 20130). It was, in the most literal sense, an album of "mood music": ten movements (labeled "love," "hate," "sorrow," "fear," etc.) expressing vastly diverse feelings. Shores was composer and conductor. It was a record album that launched Shores' career in Hollywood. Mercury Records, in early 1957, released an orchestral LP called Emotions (Mercury MG 20130). It was, in the most literal sense, an album of "mood music": ten movements (labeled "love," "hate," "sorrow," "fear," etc.) expressing vastly diverse feelings. Shores was composer and conductor.

"That album got me started," Shores noted. He moved to Los Angeles with his family and, he remembered, "I hadn't worked for about nine months after we came out here." Composer David Buttolph ("practically the only composer I knew in Hollywood") suggested he meet with talent agency MCA's Abe Meyer. Meyer had heard Emotions, and it clearly demonstrated Shores' inherent dramatic sense. By 1959, Shores was working in television. (As a postscript, Mercury reissued Emotions in late 1959 under the considerably more sensational title Music to Read Lady Chatterley's Lover By!) One of his first assignments was to create an entire library of music for one of Four Star's several series on the air: Richard Diamond, Private Detective. "I did a session for Four Star," Shores recalled. "At that time, Herschel [Burke Gilbert] went to Europe and did a whole bunch of music. I remember one Sunday afternoon at Herschel's house, he had about 15 different composers over there. And the whole idea was this: He would pick you, and decide what show he wanted you to do, and you would write maybe a half-hour of music. All different kinds of cues, including a main title. You had never seen the show, of course. So I drew Richard Diamond, with David Janssen. That thing ran for a long time. It still runs all over the world." Gilbert was Four Star's music director, and as such commissioned various composers to write music that would fit a variety of dramatic situations and then be "tracked" by music editors throughout a show's entire season. The scores were always written for full orchestra and conducted by Gilbert in Munich. (The practice of tracking has since, for the most part, been abolished by the musicians' union.) This was for the fourth season of Diamond, 1959-60. Pete Rugolo had scored the previous season, but a dispute over publishing rights led to the series' dropping Rugolo and starting fresh with new music. Shores came up with a fast-paced, percussive chase theme and a sexy saxophone motif for the suave private eye; together they made up the new Diamond theme, and the basis for much of the library. But it was at Revue Productions (later and better known as Universal Television) that Shores found steady employment for nearly four years. His first assignment was the Audie Murphy series Whispering Smith, a half-hour western produced in 1959 but not aired by NBC until the summer of 1961. "It had a lot of violence; the League of Decency was after that show," Shores recalled. He scored 15 episodes in all, including the theme. Revue music director Stanley Wilson kept Shores busy, mostly in the "oater" genre. "I got so sick of westerns," Shores confessed, and with good reason: He wrote the music for 12 hour-long episodes of Wagon Train starting in the fall of 1960; 13 Tales of Wells Fargo beginning in mid-1961; plus four episodes of Laramie and four of The Virginian, all of which stretched into 1963. Shores' very first Wagon Train was also his most memorable. Film star Charles Laughton made only a handful of television appearances, one of which was a Wagon Train called "The Albert Farnsworth Story," about a haughty British colonel who was constantly tangling with an Irishman in the group; Shores incorporated some colorful faux-English and -Irish material into his score. Private-eye shows got the Shores treatment, too: Thirteen episodes of Edmond O'Brien's syndicated half-hour Johnny Midnight, done in 1960; plus two episodes of Checkmate, in 1962. He also scored one installment of the classic Alfred Hitchcock Hour ("Ride the Nightmare," which aired in November 1962, the sole Hitchcock to have been written by fantasy author Richard Matheson). There was a brief sojourn into features, neither very successful: the folksy Universal pickup Tomboy and the Champ, about a Texas girl and her prize-winning calf, and the peeping-tom melodrama Look in Any Window starring Paul Anka as a troubled teenager. Both were released in 1961. © 2004 Jon Burlingame Related Articles: Richard Shores Remembered, Part I Richard Shores Remembered, Part II Richard Shores Remembered, Part III |

Search

Past Features

Feature Archives

|