|

|

Print this article Print this article

FMS FEATURE ARTICLE...

November 26, 2004

David

Remembrance of a treasured friend

by Jon Newsom

Chief of Music Division, The Library of Congress

David Raksin, 1915

In grammar school operetta, 1925

|

|

Editor's note: This personal reminiscence was

originally published in the program of a memorial service for David

Raksin on November 15, 2004 in Los Angeles, California.

Music is not translatable into words, yet, in the context of a

dramatic or poetic setting, it can, in the hands of such a master as

David Raksin, achieve expressive depths possible in no other art,

depths which probe the ineffable realm of human feeling with an acuity

impossible in words or pictures.

Yet words are all I am able to offer even though there is no word,

perhaps not even an evocative combination of words, that summons up a

particular feeling in David's best music of which I want to speak.

That feeling is melancholy but not sad, noble but not arrogant,

longing but not grasping, sentimental but not self-indulgent, resigned

but not despairing. Its passion is not suppressed yet it is poised,

even philosophical. The dark prophet Ezekiel might even find momentary

solace in its strains. Tristan and Isolde might hear in it the

troubled voice of King Mark. From where, one wonders, did this depth

of feeling come?

Frederick Delius, whose music, if not his character, David and many of

his generation admired especially for its harmonic richness, created a

mood both aspiring and sensual, and in a spirit of resignation

nurtured by the Dionysian philosophy of Nietzsche and the romantic

writings of the Danish poet Jens Peter Jacobsen. This hedonistic ethos

of a turn-of-the-last-century cult, however, was alien to David, who

was too much of a Jewish patriarch to permit its licentious undertones

to infect the noble despair and anger he felt as a tone-poet and

toiler in Jehovah's vineyards. Though not a conventionally religious

man, David had a more vivid image of God than most people I know, and

he was highly sensitive to the injustices his Creator could inflict,

not so much on himself but on his fellow men and women. Like Job,

David felt that his own ethical vision was superior to that of his

Maker.

|

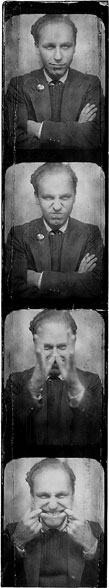

Photostrip taken during production of Transatlantic

Rhythm, captioned by David: "Monkey Bizness on the

Irish Sea" Sept. 1936, Blackpool

|

On saying this, I now hear in my mind's ear David's voice from the

beyond, filled with fatherly caution but not without nuances of

guarded approval such as one uses in addressing a zealous but

unseasoned disciple. He is saying to me: "Jon, you may be slightly

overstating the case." Yet I hear as clearly his voice the night more

than twenty years ago when we were discussing one of his favorite

characters, King Oedipus. The conversation turned logically and

passionately to another favorite fatherly character who was equally

buffeted – some believe by Fate, others by Fate's more willful

personification in the form of the Heavenly Father. I am speaking of

course of Abraham, Father Abraham who belongs to all inheritors of the

great desert religions. David knew exactly what he would have said to

God if ordered to sacrifice his only son, and he vented and I listened

with as much compassion as he had shown me when I was the outraged

friend in need of an understanding ear. And I urged him, with all my

powers as a commissioner of new music with money to offer, to set his

rage to music, or at least to consider setting one of Kierkegaard's

several variant versions of the story, each more horrendous and – as

David would say – "heart-rendering" than the preceding. Even better, I

suggested, take Benjamin Britten's approach and use Wilfred Owen's

version in which Abraham refuses not the Lord's but the Angel's

intervening command to hold his sword, and so, the poet writes, "slew

his son, and half the seed of Europe one-by-one." Unfortunately, David

did not feel up to the challenge.

David, 1940s

|

|

The urbane, wistful longing of Laura, the themes from The Bad

and the Beautiful, Forever Amber,

Too Late Blues, Carrie, or

Will Penny were not born, if anyone might suspect

they were, out of the sheer talent of a master craftsman in fulfilling

the demands of his profession, but out of David's compassionate and

embattled heart which sought to understand the pain felt by the loving

and complex people in the films he enriched and, to a great extent,

interpreted for their audiences and often, to their chagrin, the very

creators of those films who had hired him. He looked into their

characters' souls and often understood them more deeply than those

writers, directors, and actors who brought them to the screen only

partially developed and emotionally inarticulate before David's music

provided the nuances that make them believable and memorable. His

world was one of searching, discovering, and playing (he loved words

as much as notes). His world was also one of changes and the endless

partings effected by change. His music was both his outlet for grief

and his consolation.

David with horns, 1950s

|

|

He said once that he lived and worked in a golden age of Hollywood,

and that he and his colleagues knew that it was a golden age and that

they lived it to the hilt. He appreciated that for a brief time, a

composer of his special genius could write the kind of music he needed

to write and, most remarkably for any time in the history of music,

hear it played beautifully and immediately.

David has left us a musical legacy unique in its expressive powers,

and too rich to be superceded by changing fashions. It is also so

universal that it can with grace and style follow the hearts of an

Apache warrior, a king's mistress, or a detective who has fallen in

love with a portrait of a beautiful woman whose presumed death by

murder he is investigating.

We will each miss David the man in our own personal way. We will all

share, however, in the musical heritage he has left us and which will

remain for us and, we may hope, for many generations to come, as a

consolation until the ends of our lives.

|

|

|

Error: DISTINCT YEAR query failed | |