|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

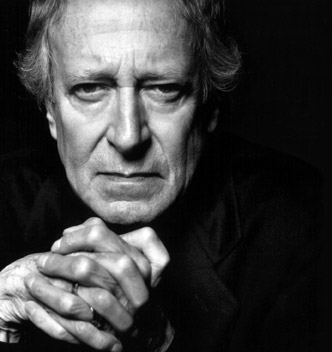

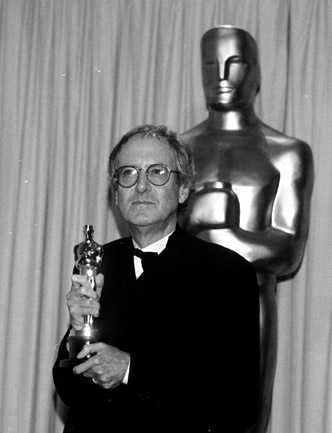

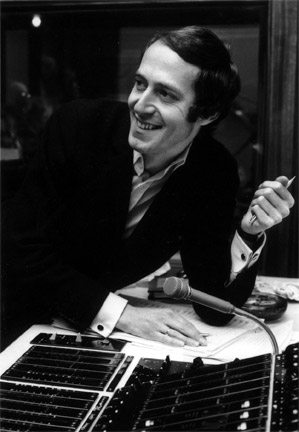

FMS FEATURE... February 2, 2011 John Barry: An Appreciation Celebrated composer's innovative film scores will always live somewhere in time by Jon Burlingame  Barry's death on Sunday marks the passing of an era. Yes, some of our musical icons from the 1960s, '70s and '80s are still around, still writing, still conducting... but the loss of John Barry is keenly felt simply because there was no one quite like him. He had the good fortune to musically launch the James Bond franchise because the twangy-guitar-driven, jazz-rock sound of the John Barry Seven was considered a commercially viable choice for the Bond theme. The result was a fresh approach for all of the 007 movies: bold and brassy, what he called "million-dollar Mickey Mouse music," not in any derogatory fashion but rather describing a lively, fun, pop-orchestral style that was perfect for the exploits of a globetrotting, larger-than-life British spy. Goldfinger, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, Diamonds Are Forever — their brash title songs and powerful scores were unlike anything we'd ever heard in the cinema. "He revolutionized film music," lyricist Don Black said this week. "John Barry is the reason I wanted to write film music," composer David Arnold wrote. "Barry was the master of encapsulating the spirit of an entire motion picture with the simplicity of a perfect theme," his longtime agent Richard Kraft said shortly after Barry's passing. Dozens of writers over the years have attempted to analyze the Barry sound — what makes his music so memorable, so unusual, so unique? "Just as you know a Sinatra song from the first few bars, you can spot a John Barry score from the opening chords," Black said. "Every tune he wrote felt like it took you to places you'd never have imagined," added Arnold. Barry's unusual musical education is certainly part of the answer. The son of a pianist and a theater-chain owner, he studied music with Dr. Francis Jackson at the great cathedral in York Minster; then augmented his classical training with a correspondence course from Stan Kenton's great jazz arranger Bill Russo. And he had years of practical experience, not only arranging for military bands in the service but also playing trumpet for his own band in the late 1950s, then writing arrangements for pop singers into the early 1960s. But his early love of movies, and all those symphonic scores by such scoring pioneers as Steiner, Korngold and Waxman, instilled in him a sense of musical drama that would play out decades later in his own music. It was also the times he lived through. He never forgot the German bombing of York during World War II, which cost him childhood friends and, he once told me, may have influenced his penchant for melancholy themes. In later years, the smart and talented young composer found himself in the midst of London's Swinging Sixties. Carousing with the likes of Michael Caine and Terence Stamp, he lived high and wild, marrying four times — although Laurie, his fourth wife, was the real thing, a union that lasted 33 years until his death. (Nobody doubts that it was Laurie's insistence on the finest medical care that saved his life after his esophagus ruptured, requiring multiple surgeries, in 1988.)  Along the way, there were the Bryan Forbes films that required a gentler touch: the alto flutes of Séance on a Wet Afternoon, the harpsichord for a lonely old woman in The Whisperers and the guitar concerto of Deadfall. And those other classic '60s scores: the massive orchestral might of Zulu, the jazz organ of The Knack, the quizzical saxophones of Petulia and the raw harmonica of Midnight Cowboy. He added choral forces to The Last Valley, Walkabout and Mary Queen of Scots. He was always on the lookout for new sounds that would add aural spice to his scores: The cimbalum lent an atmospheric, vaguely Eastern European touch to The Ipcress File; a Moog synthesizer updated the sound of James Bond in On Her Majesty's Secret Service; and a mandolin added Continental colors to The Adventurer. Perhaps the masterpiece of all these sonic explorations was his theme for TV's The Persuaders!, the lighthearted Tony Curtis-Roger Moore romp: He combined cimbalum, the Finnish kantele, mandolin and mandola, with electronic keyboards and rhythm section for a stunning, never-equalled television signature that spent longer on the British charts in 1971 than Barry's recording of the Bond theme had done in 1962. Later years brought a more sedate, romantic sound to the Barry output, including the touching Robin and Marian, emotionally rich scores for Somewhere in Time and Out of Africa, and his sweeping, multi-thematic tone poem for the still-unspoiled Western frontier, Dances With Wolves. Yet he could still reach back to his jazz roots for movies like Body Heat, The Cotton Club and Playing by Heart. The tributes pouring in from around the world have necessarily focused on the film work, but there was so much more that deserves exploration and examination. Of his five stage musicals, only one (Billy, with a pre-Phantom of the Opera Michael Crawford) was a massive West End hit. But he collaborated with Alan Jay Lerner on Lolita, My Love and later tried to mount the children's classic The Little Prince on Broadway; both conceptually flawed but daring artistic choices that, someday, may be widely heard. Even his made-for-television movies were special: The fragility of his piano theme for The Glass Menagerie, the grandeur of Eleanor and Franklin, the nostalgic charm of Love Among the Ruins (in which Laurence Olivier himself sang the theme). In person, John Barry was warm and friendly, open and often very funny. He was a private man, to be sure — he had enjoyed a very public persona back in the 1960s but for the past three decades preferred the quiet life in Oyster Bay, N.Y., halfway between Los Angeles and London. If pressed, he could regale you with tales of Harry Saltzman's hatred of the Bond songs, of informing Barbra Streisand that he wasn't going to stand for tampering with his music, of trying to write King Kong reel by reel in order to make the release date, of the constant search for new sonorities, new flavors, new thematic ideas. Ask about those Swinging Sixties, he would try and steer you away from the topic as overrated, but the twinkle in his eye also told you he was glad to have participated. I interviewed him often over the past 25 years, most recently for a special Variety section in 2008 on the occasion of his 75th birthday. We were with him at Carnegie Hall for the live concert performance of The Lion in Winter in 2004, and then became among the privileged few to hear his new song score for the short-lived Brighton Rock musical during its six-week tryout later that year in London. But no thrill may ever top being present for his triumphant return to public performance, conducting the English Chamber Orchestra before a sold-out Royal Albert Hall crowd in 1998. As the London Times' Caitlin Moran put it at the time: "The three standing ovations he received were the most devoted clappings I've ever seen in my life. From up in the circle, it looked like praying. Entirely understandable." For me, the obscure recordings resonate as much, if not more, than the big hits: The soaring "Girl With the Sun in Her Hair," originally written for a shampoo commercial; tracks like "Who Will Buy My Yesterdays" and "The More Things Change" from Ready When You Are, J.B.; the magnificent choral-and-orchestral tapestry of James Clavell's Thirty Years War saga The Last Valley; the haunting title tune of his failed musical Lolita, My Love; the gorgeous ballads in his only film musical, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland; the evocative, bittersweet scores for films like Chaplin and Swept From the Sea; and his autobiographical concept albums Americans, The Beyondness of Things and Eternal Echoes. These three albums, especially, capture the personality of the man as much as any writing about him could. Earlier this week, Richard Kraft offered this startling revelation:  We have lost one of the true giants of the last 50 years of film music. But the legacy of John Barry — that extraordinary canon of themes, scores and sounds unique to the man and his times — remains. Future generations, just discovering Barry's music, will envy us; they will only be able to imagine how exciting it was to hear a new John Barry score for a film, a television show, a stage musical or an album. How lucky we were. ©2011 Jon Burlingame John Barry was born on November 3, 1933, in Yorkshire, England and died of a heart attack on January 30, 2011, at his home in Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York. |

Search

Past Features

|