|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

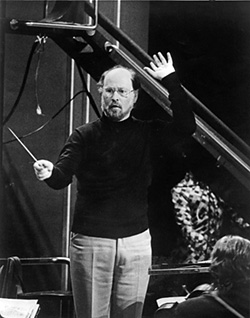

FMS FEATURE... October 10, 2012 E.T. Turns 30 Williams' score soars on new Blu-Ray release by Jon Burlingame  Composer John Williams' music for E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial is one of the best-loved film scores of all time. It soars. It's powerful. And most of all, It plucks at the heartstrings. He spent three full months composing and recording that now-legendary music. Three decades later, what Williams recalls of that time is how difficult the task was and how hard he worked to achieve those lofty goals for his longtime filmmaking partner Steven Spielberg. For its 30th anniversary, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial is released on Blu-Ray this month in all-new 7.1 surround sound that is expected to showcase Williams' Oscar-winning score in greater brilliance than ever before. "At the time I was working on it," Williams told us recently, "I don't think I really realized how truly great that film is. It sets the most magical story in the most mundane of circumstances: the suburbs, a broken marriage, a couple of interesting kids. This little creature hidden in the bedroom, falling in love with these young Earthlings and vice versa – an unbelievable story told so skillfully, so expertly, that you buy it completely." Williams' music is no small part of that accomplishment. E.T. was Spielberg and Williams' sixth film together, including landmark scores for Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). And at the time he composed E.T., he was just a year into another new and challenging job: serving as music director for the famed Boston Pops Orchestra. "I was working very hard at that point," he recalled. "I remember Steven mentioning E.T. quite a few times when we would have dinner," Williams said. "He had this idea about a child and an extraterrestrial; he was working on the script with Melissa [Mathison], which sounded wonderful." When the film was in rough-cut form, Williams screened it and began working on musical ideas. "The process was then, and still is, Steven will come over and I will play him sketches on the piano, sometimes just a few bars." The director gave his approval; Williams went off to write the complete score; and Spielberg joined the composer and a nearly 80-piece orchestra for the recording sessions in April 1982 at the old MGM scoring stage in Culver City, Calif. Williams' score revolves around five main themes: a sweet and charming theme for the stranded alien, first heard on piccolo; a touching piece for the unique relationship between Elliott (Henry Thomas) and E.T., ethereally expressed by the harp; dark and sinister music for the government agents seeking the stranded alien; "traveling" music for the boys on their bikes; and the "flying" theme, an orchestral tour de force for E.T.'s grandest demonstration of his powers. "I remember working very hard on that flying theme," Williams said. "I was concerned about getting just the right, soaring melody, which for me as a musician was a serious challenge. Here were kids flying on bicycles over the moon — completely believably – and what would the orchestra say? What would the leaps of melody be? What could possibly be good enough to accompany a film like this?" The composer, of course, rose to the challenge. And what's more, Spielberg went the extra mile to ensure that Williams could make just the right musical statement, especially during the climactic bike chase leading up to the finale and E.T.'s departure. The entire sequence runs nearly 15 minutes – a very complicated piece of music with specific synchronization requirements throughout. During the recording, he attempted to conduct the entire piece from start to finish but, he recalled, he kept missing certain key sync points. Williams was attempting to balance the picture-specific needs of the film with the finest musical performance he could elicit from his musicians. During a break, Spielberg suggested the composer stop conducting to the action on the screen. He urged Williams to play the music as if in a concert, and promised to adjust the edit later to match the music. "Which is exactly what happened," Williams said. "He cut the film to the orchestra track." It was a rare instance in Hollywood of a director allowing an extraordinary piece of music to override visual considerations. As a result, Williams believes, there is "an intimate connection between picture and music that I don't think the greatest expert in film synchronization could quite achieve. There is an ebb and flow, where the music speeds up for a few bars, then relents, the way you would conduct for a singer in an opera house. There is something visceral, organic, about the phrasing. That last 10 minutes delivers something, emotionally, that is the result of the film fitting the music, and not the other way around, I am delighted to say." That "visceral, organic" feeling was never more palpable than at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles on March 16, 2002, when Williams conducted the entire score in a live-to-film performance to celebrate E.T.'s 20th anniversary. "I've never done that before, or since," Williams said. "It's a fabulous event for audiences, something I wish we could do more frequently." Williams won the fourth of his five Academy Awards (as well as three Grammy Awards) for the music of E.T. It ranks in the top 15 of the American Film Institute's all-time best film scores. There have been three different album configurations of E.T. over the years (nearly every note of the 76-minute score has now been released). And it still thrills audiences when Williams conducts it live in concert. Composer and director have gone on to do 26 films together, a creative collaboration over 40 years that also includes Jurassic Park, Schindler's List and the forthcoming Lincoln. But E.T., Williams suggests, "may be Steven's masterpiece." Speaking recently at Williams' 80th birthday celebration at Tanglewood, Spielberg called his friend "this nation's greatest composer and our national treasure. He has given movies a musical language that can be understood in every country on this planet. Without question, John Wiiliams has been the single most significant contributor to my success as a filmmaker." ©2012 Jon Burlingame |

Search

Past Features

Feature Archives

|