|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

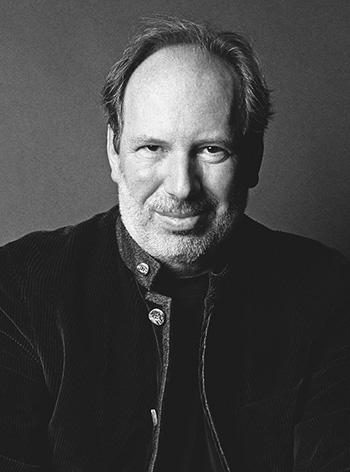

FMS FEATURE... November 6, 2014 Hans Zimmer's Interstellar Adventure Composer unveils secrets of organ, choir, orchestra in Nolan film by Jon Burlingame  Photo by Zoe Zimmer It was, according to Zimmer, the director's idea. They have done four previous films together, including the Dark Knight trilogy and Inception, all "in a certain musical vocabulary." For Interstellar, they decided to dump "the action drums, the propelling strings," as the composer puts it. "Our conversation really turned to, what's this movie about? Celebrating science. "By the 17th century," Zimmer points out, "the pipe organ was the most complex machine invented, and it held that number-one position until the telephone exchange. Think about the shape of it as well: those pipes are like the afterburners of space ships. And very little, other than Gothic horror movies, has recently been written for the pipe organ.  Zimmer and Nolan have become close friends over the past 10 years of collaboration, so the composer actually began thinking about the music two years ago. It started, "in typical Chris Nolan fashion, with a surprise," he quips. Nolan asked Zimmer to read a one-page story and spend a day composing a theme in response. "He gave me this letter that he had written on a typewriter, not a computer or a word processor. It was this beautiful fable about a father-son relationship. Now he happens to know my son very well, and my son is going to be a scientist. It was very personal, and very intimate. I did exactly as he asked." Finishing about 9 p.m., he phoned Nolan, who promptly visited Zimmer's studio. "I played him the piece, without actually looking at him. As a composer you are very fragile when you play your music for the first time. So I finished, turned around and said, 'What you do think?' He paused and said, 'Well, I suppose I'd better go and make the movie now.' And I said, 'Great, but what is the movie?'" Then, for the first time, Nolan began describing his idea for "this vast canvas," as Zimmer put it. Confused, because he had written "this tiny, intimate piece" for a parent-child story, Zimmer questioned its relevance. "Yes," Nolan responded, "but now I know what the heart of the movie is." That original piece is the music that moviegoers will hear at the very conclusion of the film, as the story ends and the credits begin to roll. It was the start of two years of conceptualizing and composing, while Nolan was writing the script and shooting the film. "We work in parallel," Zimmer explains, "so by the time he finishes the cut there is actually a complete score in the movie. Yes, it was all done on my computers and my synthesizers. And there was a certain quality about it, a singularity, because I played every single note myself." Yet Zimmer's score still needed to be performed by real musicians. The composer knew what organ he wanted: the 1926 four-manual Harrison & Harrison organ in London's 12th-century Temple Church, played by the church's current director of music, Roger Sayer. "There was a moment where there was some hesitation," Zimmer admits, "but that's the whole point, isn't it? Our job is to come up with things that people can't imagine. "We went to London and quietly made a pact: If we got even one great note out of that organ, we had fulfilled our mandate." Zimmer wasn't sure what he had written could even be realized on that instrument. "Organs are, by nature, incredibly complicated beasts," and he wanted it to be "incredibly virtuosic. As soon as Roger started to play," Zimmer adds, "both Chris and I knew, this was going to work. Roger was our star." Zimmer added an ensemble of 34 strings, 24 woodwinds and four pianos – some recorded in the church, others at George Martin's AIR Lyndhurst Hall. Then he added a 60-voice mixed choir. Most of the actual recording was done in late spring of this year. The concept of air and breath resonates throughout the score, fittingly for a movie that spends so much time with astronauts in spacesuits. He asked Richard Harvey (who, with Gavin Greenaway, conducted the score) to assemble a group of top woodwind players, then asked them to make strange and unusual sounds with their instruments. Zimmer was amused by Harvey's later remark: "You know, they've worked their whole lives never to sound like this." The choral elements were also experimental. "There is an enormous amount," Zimmer says, "but I use them in strange ways. I wanted to hear the exhalation of 60 people, imagining the wind over the dunes in the Sahara. I got them to face away from the microphones, and used them as reverb for the pianos. The further we get away from Earth in the movie, the more the sound is generated by humans – but an alienation of human sounds. Like the video messages in the movie, they're a little more corroded, a little more abstract." At the end of the process, Nolan presented Zimmer with a watch much like the one that plays a key role in the film's story about the pilot (Matthew McConaughey) and his daughter (Jessica Chastain). Inscribed on the back was the phrase "this is not a time for caution" which, Zimmer said, "was pretty much our motto all the way through. Everything we did, we tried to approach with a sense of adventure." Stylistically, it veers from late 19th-century Romantic gestures to late 20th-century minimalism. Zimmer wrote more than two hours worth of music, although he was reluctant to estimate how much is in the final cut of a film that runs 169 minutes. That's the composer himself playing the solo piano for the scenes near Saturn. Ironically, for a movie titled Interstellar, Zimmer says, "this score is incredibly personal to me. How much more personal can you get when somebody says to you, 'Write about your children's future'?" ©2014 Jon Burlingame |

Search

Past Features

|